Asset managers and their customers want different things

- Robin Powell

- Jan 12, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 6, 2024

By ROBIN POWELL

There are so many books on asset management. Far too many in fact. Almost all of them focus purely on investing, and most are written by asset managers themselves, eager to sell their wares.

For me, investing is the least interesting aspect of asset management. The evidence clearly shows that very few funds, if any, succeed in beating the market in the long run on a cost- and risk-adjusted basis. When they do outperform, distinguishing genuine skill from random chance is extremely difficult. So buying a book on a fund manager’s “secrets” is highly unlikely to help you improve your own returns.

Of far more interest to me is the business of asset management. It’s a sector that has grown exponentially in recent decades, and it’s not hard to see why. Rising markets, increased life expectancy, tax incentives for long-term investing and the growing onus on individuals to prepare financially for retirement have all played a part.

How refreshing, then, to read The Economics of Fund Management, a book that focuses almost exclusively on the industry itself, how it operates and how it makes its money. It’s refreshing too that, unlike other books on this subject which tend to focus on the US, this one looks mainly at the UK and Europe.

Another reason to read this book is that it’s written by someone who was once on the inside. Now an Associate Editor at Ignites Europe, part of the Financial Times Group, the book’s author, Ed Moisson, spent 16 years working in the industry, mainly as an analyst, before becoming a journalist.

Misaligned interests

The book is full of fascinating insights, but a common theme runs throughout. Simply put, the interests of the industry and its customers are, to a large extent, mutually exclusive. As Moisson explains in his introduction: “This is the inherent tension, and potential conflict of interest, that asset managers must grapple with, but which they prefer to downplay: higher fees for the business mean lower returns for clients, all other things being equal.”

Fund charges, Moisson explains, really do make a huge difference to consumer outcomes.

“Some readers,” he acknowledges, “may find the extent of the focus on this issue slightly surprising.” But, he goes on, it’s justified because cost has “a direct and cumulative impact on the returns investors receive, i.e. the reason for investing.”

The problem, he says, is that “retail investors in the main do not understand the importance of charges and, even if they did, they lack influence in affecting change in this area”.

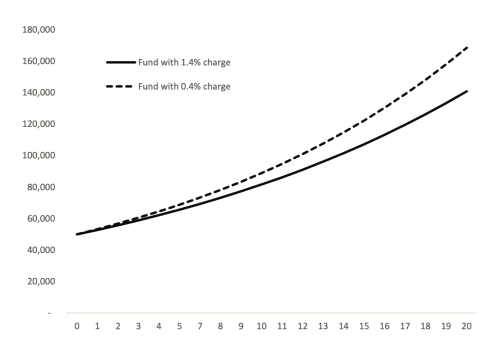

The author illustrates the importance of cost using the chart below. It shows the drag effect over a 20-year period on two funds with different annual charges — one charging 0.4%, the other 1.4%.

Based on an original investment of £50,000, and assuming annual growth of 7% before costs, the cheaper fund delivers £27,612 more than the costlier one. If £500,000 had been invested, the difference would be £276,116.

Good news and bad news

So even very small reductions in fees produce significantly better returns for investors. But they also make a substantial difference to the income that fund managers generate.

The good news is that fees for actively managed funds have come down to some extent, but active funds are still far more expensive than passively managed index funds. What’s more, there’s very little evidence of fund managers passing on economies of scale.

The larger a fund is, the more fees it generates. “As a result,” Moisson writes, “an asset management company is, in principle, incentivised to grow its assets both through generating returns (performance) and through attracting and retaining clients (sales).

“Manager and client interests are aligned in wanting to generate higher returns, but this is not the case for client inflows. For some investment strategies an ever-larger asset pool can be detrimental for the delivery of the intended level of performance.”

And it gets worse. Some UK asset managers, the book explains, have “doubled down” on their policy of making disproportionately higher revenues from managing larger funds. “They have done this by fixing their ongoing charges, in other words, setting a fixed percentage charge that covers all costs, not just the management fee. This has been sold as a boost for transparency (but it) is also a way for the asset manager to generate higher fee.” Why? Because “if the costs incurred by the fund are less than the money raised from the percentage charge then the asset manager pockets the difference”.

This practice, the author notes, has been allowed to proliferate, apparently unchecked by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Simple solution

As we’ve said on this blog many times, asset managers could stem the flow of assets from active funds to passively managed ones by simply lowering their fees. Indeed, they’re coming under increasing pressure to do just that.

But, says Moisson, they’re unlikely to give into that pressure any time soon. Salary levels remain very high compared to other professions (the mean pay level, for all employees, including admin staff, is close to €200,000); profit margins are eye-watering too (typically between 34% and 39% according to an FCA report in 2016).

Another obstacle in the way of lower fees, the author claims, is groupthink:“(Fund managers) struggle to think beyond what is accepted industry practice.”

But things can’t go on indefinitely as they are. Without more price competition, the huge net inflows into low-cost index funds we’ve been seeing will continue, and the active fund industry will only have itself to blame.

It’s thanks in no small part to journalists like Ed Moisson that these crucially important issues are finally being debated.

The Economics of Fund Management by Ed Moisson is published by Agenda Publishing.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIV. All rights reserved. Unauthorised use and/ or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited.