Amid fears over rising inflation and interest rates, many investors are looking to hedge against those risks. A commonly held view is that, at times such as these, dividend-paying stocks provide more income protection and higher returns than stocks that pay small dividends or no dividends at all. But is that view supported by academic research? LARRY SWEDROE has been analysing the evidence.

The unprecedented increase in money creation and extraordinary expansionary fiscal spending around the globe, combined with the supply considerations arising from both COVID and the invasion of Ukraine, have led to heightened concerns about inflation risks. Not surprisingly, many investors are seeking to hedge their portfolios against those risks. But what's the best way to do it?

While many investors believe that equities have provided a hedge against inflation, research papers such as the 2021 study The Best Strategies for Inflationary Times and the 2022 study have found that equities have only “worked” over a very long time horizon (because of the equity risk premium). They have actually been a negative hedge in shorter time frames, tending to fall when inflation rates rise (as the rate used to discount future earnings increases with increased economic uncertainty).

That’s the evidence for equities in general. But what about relying on dividend-paying stocks as a hedge against inflation, hoping to receive more income protection and higher returns? In January 2022 investors poured $7.5 billion into funds that buy dividend-paying stocks, the most on record. To determine if that is a reliable strategy, the research team at Dimensional examined the performance of dividend-paying stocks over the period 1928-2021, focusing attention on periods of high inflation (defined as greater than that of the full sample median, 2.68 percent) as well as periods of rising interest rates (using the three-month Treasury bill).

The report's authors began by noting: “The percentage of firms paying dividends has declined globally as 68% of US companies were paying dividends in 1927, while only 38% of firms paid in 2021.” Thus, by focusing on dividend-paying stocks, investors sacrifice some of the benefits of diversification.

The researchers added this caution: “A dividend-focused strategy does not necessarily provide stable income. In fact, changes in dividend policy are common, especially during times of higher uncertainty. For example, many dividend payers cut their dividends during the pandemic — in the first three quarters of 2020, dividends from each dollar invested in US markets decreased by 22% compared to the same period in 2019.”

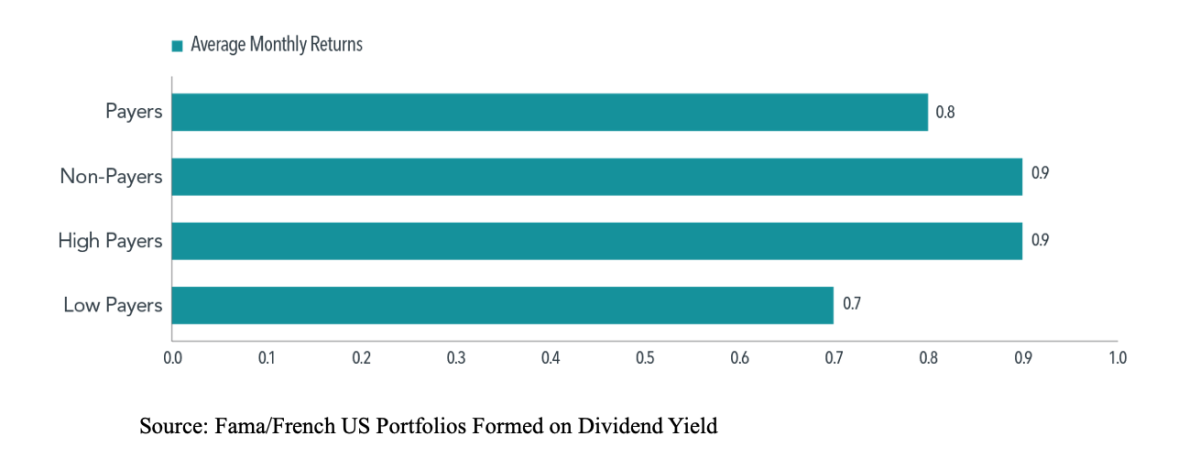

Dimensional divided U.S. companies into two groups, payers and non-payers, at the end of each June, based on whether or not they paid dividends during the previous 12 months. Then, within the payers, high payers were defined as the 30 percent of firms with the highest dividend yields, and the low payers were the bottom 30 percent. Not only did Dimensional find no clear pattern between the level of inflation and the difference in performance between payers and non-payers, but as you can see in the chart below, non-dividend payers outperformed both low payers and high payers:

Dividend-paying stocks in periods of rising interest rates

Dimensional next looked at how dividend-paying stocks performed during periods of rising three-month Treasury yields. As you can see in the chart below, they found that dividend payers, non-payers, high payers and low payers all had similar average monthly returns from March 1934 to December 2021:

Dimensional found similar results when using the effective federal funds rate and 10-year Treasury yields. In other words, "piling into dividend stocks would not have led to superior returns in months with rising interest rates.”

The researchers concluded that whether using the fed funds rate, three-month bills or 10-year Treasuries, there was no discernible relationship between interest rate movements and the relative performance of dividend payers over non-payers, or high payers over low payers, in the same month.

Their findings led Dimensional to conclude: “There’s no strong evidence that dividend stocks have delivered superior inflation-adjusted performance during periods of high inflation or rising interest rates.”

Before concluding, we will take a deeper dive into the theory and empirical evidence on the relationship between dividend-paying stocks and inflation/rising interest rates so that we might understand why those stocks did not outperform during periods of rising inflation and/or rising interest rates, as many would have expected.

Dividend-paying stocks and sensitivity to interest rates

The traditional view in finance is that stocks that pay dividends are to interest rates because the duration of their cash flows is shorter than for non-dividend payers. By paying dividends, a firm provides cash flow sooner to investors than one that only pays cash when the stock is sold; hence, the duration is shorter.

High-growth firms tend to have lower dividend payouts but higher future growth rates. That skews the distribution of their cash flows toward the most distant future. In contrast, firms with higher dividend payouts tend to have lower retention ratios and lower future growth rates. Thus, the timing of their cash flows is relatively sooner. As a result, a valuation model predicts that duration tends to be higher for stocks with lower dividend payouts. Thus, we should expect that dividend-paying stocks, especially those paying relatively high dividends, will be less sensitive to interest rate risk. What does the empirical evidence show?

Hao Jiang and Zheng Sun, authors of the 2015 study Equity Duration: A Puzzle on High Dividend Stocks covering the period 1963-2014, found that the data was in direct opposition with traditional theory. They found that “the duration of the portfolios increases monotonically with the dividend yields. Stocks with high dividends tend to experience decreases in returns when long term bond yields increase, while those with low dividends tend to earn higher returns when interest rates hike up.”

During the period studied, when interest rates declined by 1 percent, high-dividend stocks experienced an increase in returns of 1.35 percent. In contrast, low-dividend stocks had a decrease in returns of 1.12 percent. And both effects were statistically significant at the 1 percent confidence level. The difference in estimated duration between high- and low-dividend stocks was 2.46, with high statistical significance. The authors found the same pattern when they used dividend payout ratios (dividends divided by book equity) as an alternative measure of dividend payments. They also found that not only did high-dividend stocks tend to have a long duration that was robust throughout the period but also that the effect was particularly strong toward the end of their time frame.

Interestingly, the authors discovered that their results weren’t caused by high-dividend paying stocks having higher betas (more exposure to systematic equity market risk). In fact, they found that high-dividend paying stocks tended to have lower betas. They also found that “despite the highly volatile correlation between aggregate stock market and bond market returns ranging from very negative to very positive the long duration of high-dividend stocks remains stable in the past five decades.”

There is one more issue related to the dividend discount model and duration we need to discuss: They don’t take into account the uncertainty of cash flows. Risky securities may be less sensitive to interest rate changes and have shorter duration because the relative contribution from distant cash payments to the present value is small when compared to a risk-free security.

The link between cash-flow risk and dividends is strongly rooted in the dividend literature. Companies are reluctant to distribute higher dividends if they face high uncertainty and may have to reduce future dividend payments due to lower earnings. This leads to dividends being negatively related to firms’ cash-flow risks. If stocks with higher dividends tend to have lower cash-flow risk, then their sensitivity to interest rate changes will be relatively greater. Investors’ view that dividend-paying stocks are safer investments lowers the discount rate and increases the duration of the cash flows, increasing sensitivity to interest rate risk. This understanding helps explain why the data conflicts with traditional theory.

Investor takeaways

Smart investors know that when a theory conflicts with the data, throw out the theory, not the evidence. As you have seen, the evidence makes clear that if you are seeking to hedge the risk of inflation, instead of chasing dividend-paying stocks, you are best served by staying disciplined and broadly diversified, which provides you the best chance of achieving your financial goals.

If you are interested in learning more about investors’ preference for dividend-paying stocks and what the academic literature has to say about the subject, I recommend reading my ETF.com article from 2017 and my Yahoo article from 2019. And for a deeper dive, I recommend Appendix D in my book Your Complete Guide to a Successful and Secure Retirement.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIV. All rights reserved. Unauthorised use and/ or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited.