By LARRY SWEDROE

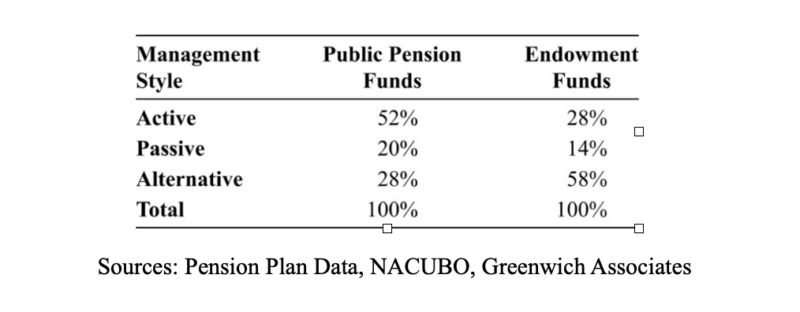

The outstanding performance of the Yale endowment fund, managed by legendary investor David Swensen, led many endowments to try to replicate its performance by increasing their exposures to alternative investments (such as private equity, private real estate and hedge funds). Today, the endowments of large educational institutions have allocations to these alternatives approaching 60 percent.

The performance of endowments has attracted great interest from academic researchers. Unfortunately, the results have not been as hoped for. The 2013 study Do (Some) University Endowments Earn Alpha?, the 2018 study Investment Returns and Distribution Policies of Non-Profit Endowment Funds, the 2020 study Institutional Investment Strategy and Manager Choice: A Critique and the 2020 study A Better Approach to Systematic Outperformance? 58 Years of Endowment Performance all concluded that factor models explain virtually all of the variation in performance of endowments, and that despite taking on more risks in the form of often opaque and illiquid investments (such as hedge funds, venture capital and private equity), there has been no evidence that the average endowment is able to deliver alpha relative to public stock/bond benchmarks. In fact, they have generally underperformed appropriate risk-adjusted benchmarks.

Richard Ennis has also done a series of studies on the performance of endowments. His June 2020 study, Endowment Performance, analyzed the performance of 43 of the largest individual endowments over the 11 fiscal years ending June 30, 2019, and found: “Endowment funds have underperformed passive investment by a significant margin during the study period, no matter how one slices the data.” In fact, not one of the 43 endowments outperformed with statistical significance, while one in four underperformed with statistical significance. He added: “Given prevailing diversification patterns and costs of 1 to 2% of assets, it is likely that the great majority of endowment funds will continue to underperform in the years ahead.”

Ennis’ August 2020 study, Three Eras of Endowment Performance Between 1974 and 2019, examined the performance of endowments (both large and small) over three distinct periods and found:

Stock and Bond Era: The large cohort composite produced an average annual excess return of -0.8 percent—the approximate margin of investment expense, including transaction costs, in that era. This demonstrates that the market in public securities was already highly efficient over the period 1974 through 1993.

Golden Age of Alternatives: The large cohort composite produced an average excess return of 4.1 percent a year for the next 15 years, primarily due to the exceptional performance of alternative investments.

Post-GFC Era: The large cohort composite underperformed the benchmark by the approximate margin of cost of 1.6 percent. Endowments were earning returns on their alternative assets commensurate with the underlying public market beta of those assets while incurring costs of 2-4 percent of asset value. Thus, alternatives ceased to be tremendous value-added sources and became a deadweight drag on performance.

Summarising, Ennis found that despite the dramatic increase in alternatives over the period, the performance of large endowments in the post-Global Financial Crisis period was, for all intents and purposes, explained by their exposure to publicly available stocks and bonds: “Notably, 99% of the variance of the large endowment composite’s returns is explained by stocks and bond indexes only. Alts had ceased to have a diversification-like influence.” He also found that small endowments performed even worse.

While these findings don’t paint a pretty picture, as Mitchell Bollinger explained in his November 2020 study, The Challenge of Endowment Performance Evaluation, the reality might be even worse due to problems of serial correlation in returns of infrequently-priced, illiquid assets. He began by noting that “a Sharpe-style asset would be the appropriate analytical tool to evaluate endowment performance if their assets were traded thereby facilitating the creation of a style portfolio with which an annual alpha could be calculated. But due to endowments reporting annually and their large concentration in alternative and non-traded assets, a style analysis will likely understate true risk and therefore overstate alpha.”

Bingxu Chen and David Greenberg, authors of the 2017 study Consistent Risk Modeling of Liquid and Illiquid Asset Returns, provide a good example of how endowment reporting understates risk. They estimated that private real estate assets that have a volatility of 4.5 percent would likely have a volatility of 9.3 percent if those same assets were publicly held. Thus, the measured volatility of private real estate understates their true risk by around half. Similarly, Ulf Axelson, Tim Jenkinson, Per Stromberg and Michael Weisbach, authors of the 2013 study Borrow Cheap, Buy High? The Determinants of Leverage and Pricing in Buyouts, found that the typical private equity fund, due to the use of leverage and exposure to higher beta investments (such as small companies) has a beta of about 2, or twice that of the broad public market. This too leads to overestimates of risk-adjusted returns.

To address this issue, Bollinger used a hybrid approach to estimate the true style portfolio for the average endowments using NACUBO (National Association of College and University Business Officers) categorisations of assets and referencing published research to map alternatively classified assets to “true” factor loadings. Following is a summary of his findings:

NACUBO asset class weights fit the average endowment return with an R-squared value of .9922—more than 99 percent of the variance in endowment returns was explained by the adjusted style portfolio.

The risk taken by the average endowment is greater than the public benchmarks. Thus, their reported performance is an overstatement of true alpha. For example, the likely true endowment style indicates that in the post-GFC era, the true debt loading of endowments was in the mid-20 percent range, which is materially lower than the 60/40 portfolio typically used for comparison to endowment performance.

The sensitivity analysis made clear that for any reasonable guess as to the true style of endowments, the 1987-1997 sub-period saw endowments slightly underperform a similar portfolio of traded assets, followed by the 1998-2008 sub-period when endowments slightly outperformed a portfolio of traded assets. During these two sub-periods, the t-statistics for almost every sensitivity indicated that the measured alpha was not significantly different than zero. The major finding is that in the 2009-2019 sub-period, endowments dramatically underperformed a portfolio of traded assets.

The estimated annual alpha for the average endowment or foundation tracked by NACUBO between 2009 and 2019 was -2.15 percent with a sensitivity range of -1.16 percent to -3.15 percent (both of which were significant at the 99 percent level), reflecting the uncertainty associated with the true portfolio style. Since the estimated cost the average endowment paid was 1.13 percent, costs didn’t fully explain the negative alphas.

Bollinger’s findings led him to conclude: “It appears that the biggest advantage to moving to non-traded assets, as has been done extensively by large endowments, is that it obfuscates the true risk factors to which endowments are exposed. This has the effect of making it challenging to facilitate a precise measurement of portfolio factor exposures and therefore the true value, alpha, created by the manager. But for any reasonable estimate of the true factor exposure of the average endowment between 2009 and 2019, the alpha generated was significantly negative.”

Bollinger urged: “Endowments need to embrace the performance evaluation methods employed in the research cited in this paper as they reflect the foremost thinking on the topic and are eminently practical.” He added: “When one zeros in on what fiduciaries should be paying attention to, alpha, it becomes obvious that endowment management is financial theatre featuring hubris, overconfidence, and obfuscation of the true risk taken and alpha generated. This theatre draws attention away from what should be the focus of fiduciary duty, that endowments are paying large fees to managers, and since 2008 have gotten dramatically less return on the true risk taken than what one would have achieved had they invested in low-cost index tracking funds that are available to all retail investors.”

There is one more important point we need to cover. In our book, The Incredible Shrinking Alpha, Andrew Berkin and I presented the evidence demonstrating that the hurdles to delivering alpha had increased, and would continue to increase, making it even more difficult for active managers to add value. Bollinger’s findings that endowment performance turned negative from 2009 onward, along with Ennis’ findings that endowment performance deteriorated sharply in the post-GFC period, provide further evidence of the increasing efficiency of the market.