By LARRY SWEDROE

The persistently poor performance of actively managed funds has led investors to shift capital away from actively managed mutual funds to passively managed funds, such as index funds, with much lower expense ratios. However, even for index funds, the expense ratio — the only observable and reported cost — is not the only significant cost investors face. Other material but unobservable and undisclosed operating costs are incurred through the trading of securities: bid-ask spreads, market impact costs and commissions. On the other side of the ledger, income can be generated through securities lending activities. Thus, two funds replicating the same index can produce different end results for investors.

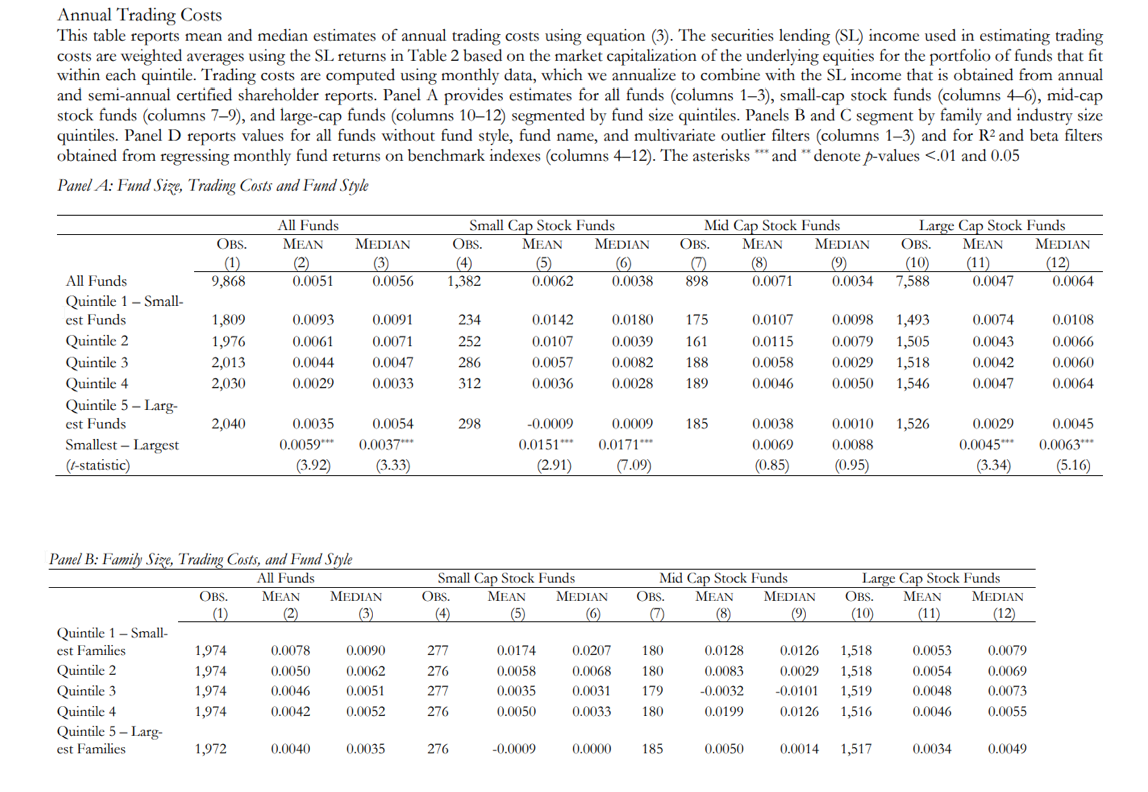

John Adams, Darren Hayunga and Sattar Mansi, authors of the study Index Fund Trading Costs are Inversely Related to Fund and Family Size, published in the July 2022 issue of the Journal of Banking & Finance, examined the role trading costs play in the returns of index funds. They estimated index fund trading costs using readily available information. The authors explained: “Because managers of index funds do not have stock picking or market timing skills, the return a shareholder earns is simply the return of the benchmark index minus operating costs plus income the fund earns from lending its securities. Fund operating costs can be divided into reported expense ratio costs (e.g., management, custodial, audit, and administrative fees), and non-reported total trading costs (e.g., price impacts from large trades, trading commissions, bid-ask spreads, and other trade-related operating costs). Therefore, while trading costs are not directly observable in actively managed funds, they can be estimated using index funds.”

They began by noting that there may be economies of scale for index funds, as larger funds from larger fund families can:

Negotiate lower trading commissions.

Invest more in smart order-routing systems that can automatically process trades at the best available execution prices and lowest costs.

Better exploit dark trading pools.

Minimise liquidity and trading costs via intrafamily cross-trading (as fund family size increases, its holdings across all funds begin to replicate the overall securities market, allowing for minimal low-cost cross-trading).

Amortise fixed costs across a larger asset base.

In addition, because larger funds tend to be members of large families that can obtain better trade execution and negotiate lower trading commissions than smaller families, family-size economies of scale likely benefit all funds in a family regardless of size—small funds in large families are likely to have lower trading costs than small funds in small families.

Their data sample consisted of U.S.-domiciled mutual funds for index funds from historical CRSP and Morningstar databases for the period 1993-2016. Following is a summary of their findings:

Trading costs of index funds are comparable in magnitude to expense ratios—annual trading costs less securities lending incomes were 49 and 53 basis points (bps), respectively, while the mean and median expense ratios were 49 and 40 bps.

The expense ratio and benchmark return gap magnitudes were mostly similar across the mid-cap and large-cap styles. However, for small-cap stock funds, the value-weighted expense ratios averaged 45 bps, but non-expense ratio operating costs were only 12 bps—suggesting that scale mitigates adverse price impacts and other illiquidity costs associated with large trades in small stocks.

There were positive economies of scale in index fund trading costs.

There were also positive economies of scale for larger funds that invest in small-cap stocks—larger funds are better able to mitigate the illiquidity constraints and higher costs associated with trading small caps. The savings in trading costs was approximately 43 bps annually for a one-standard-deviation increase in the small-cap fund size.

Their findings led Adams, Hayunga and Mansi to conclude: “Operating efficiencies associated with family-level scale are responsible for trading costs positive economies of scale.” They added: “Our findings imply bigger is better for the efficient allocation of passive investment capital.”

Scale isn’t the only factor

As Sida Li demonstrated in her November 2021 study, Should Passive Investors Actively Manage Their Trades?, how passive funds implement their trading strategy impacts their costs. For example, she found that funds that tracked public indices and pre-announced their rebalancing trades (trading entirely on reconstitution days at closing prices) had execution costs that were three times higher (67 bps) than what was paid in similar-sized institutional trades. On the other hand, funds that camouflaged trading (spreading out their trades across 10 days) saved 34 bps per trade, or 7.3 bps per year. And funds that used self-designed indices to avoid pre-announcements of rebalancing stocks saved 30 bps per trade and 9.6 bps per year. (Note that the alternative rebalancing schedule did lead to a random tracking error of 10.6 bps per year.) Clearly, the savings from intelligent trading are not insignificant. As Li noted: “Vanguard believes that the daily reporting of ETF holdings can encourage front-running and free-riding by opportunistic traders. Therefore, Vanguard ETFs publish only month-end portfolio data with 15-day lags.”

Investor takeaways

For investors, there are two takeaways. First, while prior research (for example, here, here and here) has documented that there are decreasing returns to scale in actively managed funds, especially in small-cap stocks, Adams, Hayunga and Mansi demonstrated that index funds have of scale in their trading costs and securities lending activities. Thus, index fund investors, as well as investors in all passive (systematic, replicable and transparent) strategies, should focus not only on a fund’s expense ratio but also its total expenses, which can be impacted by economies of scale. For example, Vanguard, the leader in indexing, certainly enjoys substantial negotiation power, internal crossing opportunities and the ability to amortise fixed costs across a large asset base. In addition, its huge menu of funds provides it with opportunities to cross-trade, minimising trading costs for all its funds, both active and passive. It also has the resources to invest significantly in technology that can lower trading costs. Vanguard has exploited those advantages—by lowering fees, they gained market share and obtained scale advantages in their trading costs, creating a virtuous performance circle. Other large fund families that implement systematic, replicable and transparent strategies, such as AQR, BlackRock and Dimensional, also benefit from their scale.

The second takeaway is that the trading strategies of index or systematically structured (passive) funds vary greatly, with the degree of transparency positively correlated with trading costs — the more transparent, the higher the trading costs. Thus, trading strategy should also be a consideration when building a portfolio, with a preference for opaqueness.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIV. All rights reserved. Unauthorised use and/ or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited.