I know almost nothing about cars. When the time comes every few years to change mine, I simply simply check the latest award-winning models and generally plump for the one that's won the most awards. OK, it's not scientific, but so far it’s worked out pretty well.

That said, I would buy an award-winning investment fund, and I wouldn’t encourage others to either. Why? Because I know too much about how fund awards work, and they're mostly nonsense. For starters, we’re supposed to invest for decades; what's the point of picking a “fund of the year”?

But there is an even bigger problem with fund awards and it’s this: the funds that consistently provide the highest (properly measured) returns in the long run, or the smoothest investment journey, almost never win an award. In fact they’re very rarely nominated.

Instead, the winners tend to be funds that appear to have delivered strong returns in the very recent past. Whether those funds will still be outperforming — indeed whether they’ll still exist — ten years from now is very much open to question.

The Rathbone Multi-Asset Strategic Growth Portfolio, for example, recently won Best Balanced Fund at the Professional Adviser 2023 Awards.

It’s one of the top-performing funds in its category. But, on a properly cost- and risk-adjusted basis, would investors have been better off with a simple, low-cost, passive portfolio containing just two funds?

ROY WALKER did the analysis and found there’s a runaway winner, and it the Rathbone Multi-Asset Strategic Growth Portfolio.

By the way, neither Roy nor I wish to single out for this fund, or indeed this fund manager, for special criticism. The intention is explain an important lesson: outperforming the market in the long run is very difficult. and, generally speaking, not even award-winning funds are able to manage it.

At the Professional Adviser 2023 Awards held in April, the Rathbone Multi-Asset Strategic Growth Portfolio S Acc GBP Fund was awarded Winner in the Best Balanced Fund category.

The PA Awards category shortlist included many famous names:

Quite an accolade for Rathbone, and solid recognition for the fund managers David Coombs and Will McIntosh-Whyte. Naturally, everyone knows that such industry awards are hard-won, with candidates being rigorously assessed against numerous criteria, under a robust process of fairness and scrutiny. (Ahem. I say this as Winner of Best Financial Planner, Open Category, in FPAS 2018 Awards in Singapore.) So, the Rathbone fund is indubitably good, as attested by the GBP £1.8 billion of investors’ money it deploys.

Benchmarking the fund

The Rathbone Multi-Asset Strategic Growth Portfolio S Acc GBP fund lies in the Morningstar GBP Allocation 60-80% Equity Category, delineating the proportion of equity holdings within the portfolio asset allocation.

The fund is further considered ‘volatility managed’, meaning that the managers aim to restrict the fund’s return volatility. According to the factsheet, this target is two-thirds the volatility of the FTSE Developed Index, which represents the capitalisation-weighted performance of 98% of listed equity in global developed markets. The fund benchmarks itself against the UK’s Consumer Price Index +3%, because “we aim to grow your investment above inflation”.

As Dan Lefkovitz of Morningstar noted in November 2020, it can be difficult to judge the performance of multi-asset funds. Benchmarking a multi-asset strategy differs substantively from a managed strategy focused on a single-asset class.

Morningstar and the FT benchmark the Rathbone fund against Morningstar’s UK Moderately Adventurous Target Allocation index, with such funds having “a mandate to invest in a range of asset types including equities, bonds, property, commodities, cash and liquid alternatives for a GBP-based investor”.

If we dig in to how the Morningstar Target Allocation indices are built, we see that although they are constituted from other Morningstar indices, the constituent weights are determined by the peer-group. They take the average asset allocations across all funds in the category, removing outliers, and then rescale the holding percentages to match a 70% equity target (in the case of the Moderately Adventurous version of the index). As Dan’s article says, “This aligns the indexes with actual investment behavior of multi-asset managers.”

The PIPS benchmark

This is the reason that Passive Index Portfolios (PIPS) are a useful approach to benchmarking multi-asset funds and portfolios. We can examine the PA Awards shortlisted funds above by plotting versus PIPS - a simple locus of on a risk-return chart.

We see immediately that over a three-year period, each of the shortlisted funds has delivered a risk-return trade-off (i.e. performance vs volatility) similar or better than the PIPS benchmark. That’s pretty good, and the shortlisting committee have apparently been wise in their selections.

But three years is a rather short period for observation, especially as a large proportion of funds in the category are designed to be stand-alone ‘all-in-one’ portfolios, or portfolio cores held for a long time.

Let’s look at five years versus PIPS (noting that fewer funds have this track record). We see in the chart below, that only two of five have outperformed PIPS.

Finally, here’s seven years. Only two of four funds are similar or better than PIPS.

This examination of multi-asset fund performance against an independent benchmark resonates with the data for single-asset funds, such as that from SPIVA. In the long run, a smaller and smaller percentage of funds will beat the benchmark. For example, in the USA Large Cap sector, 25.73% of funds outperformed the benchmark (S&P 500 index) over three years, but only 8.59% outperformed over ten years. For fifteen years, the figure is 6.60%.

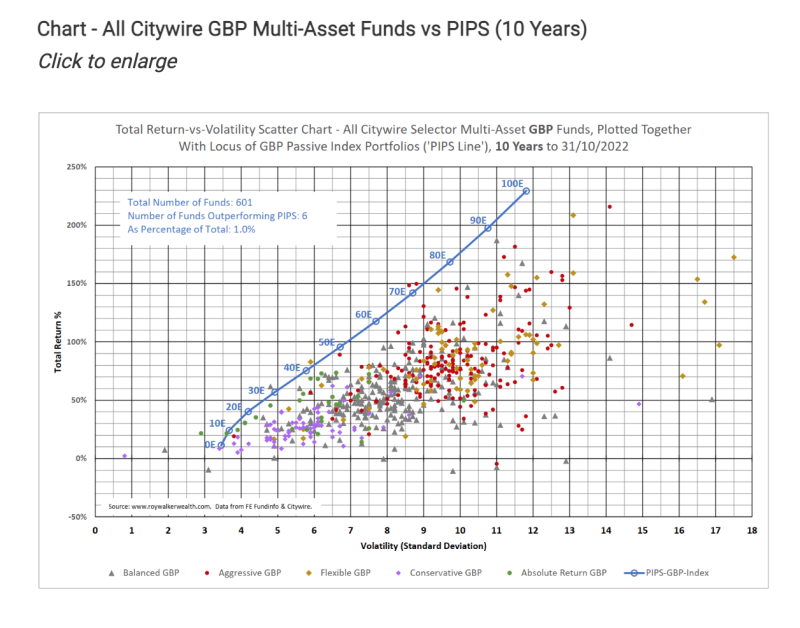

When I looked at ten years of data for every GBP multi-asset fund on Citywire, only 1% of 601 funds outperformed PIPS.

Choosing a suitable PIPS benchmark

If we plot the Rathbone Multi-Asset Strategic Growth fund versus the PIPS line for a ten-year period, to select a suitable individual index to use as benchmark, we could select the “Walkers PIPS GBP Index 55E”, as it has approximately similar volatility.

This ‘55E’ PIPS benchmark is 55% MSCI World Index combined with 45% Bloomberg Global Aggregate Hedged-GBP, rebalanced annually. This is one of the simplest 55% Equity / 45% Bond portfolios possible.

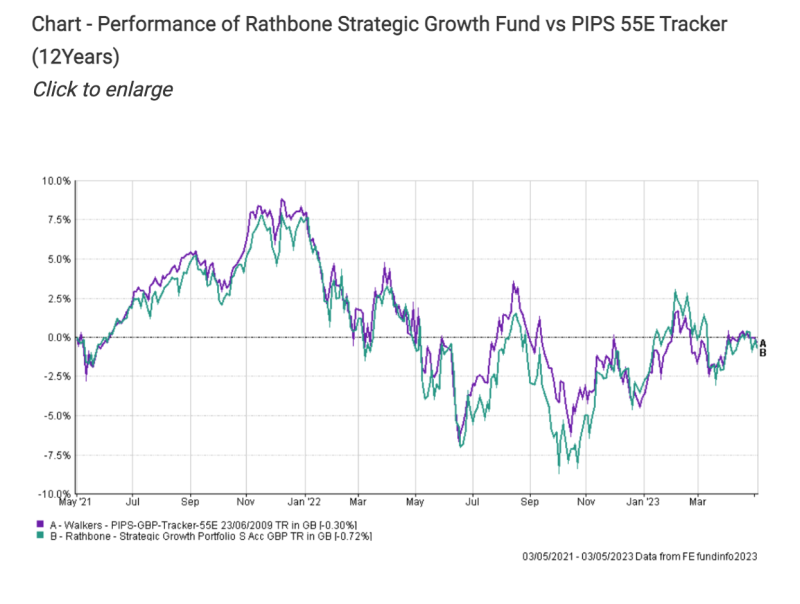

Here’s the relative performance of the Rathbone fund versus our selected PIPS benchmark, from start of data.

We see that the Rathbone Multi-Asset Strategic Growth Portfolio A Acc GBP fund has not outperformed the PIPS benchmark. I am not saying that Rathbones is a bad fund, just that the PIPS-55E index is probably a valid benchmark. The volatility is almost identical, and correlation is a positive 0.91 over ten years.

Because the Rathbone fund is a real-world managed fund with fees and costs, it will be interesting to see comparative performance versus an investible tracker of the PIPS benchmark.

Comparing the Rathbone fund with an investible PIPS tracker

Since PIPS benchmarks are constructed from indices, they are not directly accessible. But the constituents themselves are easily investible. One implementation of a Walkers PIPS GBP Tracker 55E would be 55% iShares MSCI World UCITS ETF plus 45% Vanguard Global Bond Index H-GBP.

Here’s a chart for ten years performance, below. Over this period, a DIY investor holding only one equity fund and one bond fund would have outperformed the Rathbone fund by 13%.

Below is a five-year performance chart. Over this period, a DIY investor holding only one equity fund and one bond fund would have outperformed Rathbone fund by 6%.

Below is a two-year chart. The performances are nearly identical.

This above is an interesting result. The last two years in global markets have been a white-knuckle ride, for both stocks and bonds. This is supposed to be the environment where active investing does better than passive investing, according to proponents.

This is staggering, because the Rathbone managers have the entire universe of global stocks and bonds to choose from, plus alternative investments and private equity, and can switch in or out of investments at any time. Whereas PIPS is just two holdings with only a single rebalancing each year.

I don’t single out the Rathbone fund for special pillorying. In fact, the opposite. If you are in the market for a multi-asset fund, actively managed by lots of undoubtably smart people, with the psychological comfort of a well-known brand, and the social proof of a fund-size in the billions, then Rathbone Strategic Growth isn’t out of place on the shortlist.

Conclusion

Managing a multi-asset portfolio is difficult. With great potential for more complexity than in the single-asset world, because managers have a huge universe of assets to choose from.

Managers of multi-asset funds and discretionary portfolios generally compare themselves against the peer-group, because independent benchmarks are scarce. This ignores the risk that the peer-group itself is silently underperforming.

This doesn’t need to be the case. Benchmarking using a independent passive index portfolio (PIPS) is a valid approach, and can help to keep focus on simplicity over complexity.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIV. All rights reserved. Unauthorised use and/ or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited.