By LARRY SWEDROE

The growth of exchange-traded funds (ETFs) has been significant since the first ones went public in 1993. By 2020, assets managed by ETFs in the U.S. alone surpassed the $5 trillion mark, about 17 percent of the total assets in U.S. investment companies. Over 3,400 ETFs have been launched, covering everything from broad-based indexes like the S&P 500 to niche investment themes, such as a trade war, cannabis, vegan products, working from home and COVID-19 vaccines.

Itzhak Ben-David, Francesco Franzoni, Byungwook Kim, and Rabih Moussawi, authors of the January 2021 study Competition for Attention in the ETF Space, noted that many ETFs, especially the early products, are transparent investment vehicles that passively replicate indexes. Given transparency, they can only compete on price and cannot tout portfolio managers’ past performance and skill or rely on product opaqueness to promise high yields and hide risks. Thus, they believed that the ETF industry offered “a unique opportunity to study how financial innovators design their products to draw investor attention in a space in which products are inherently simple and transparent.” They noted that funds can either compete on price, or they can compete on quality and/or uniqueness.

Their data sample consisted of all equity ETFs traded in the U.S. equity market and covered the period 2000 through 2019. They classified broad-based ETFs as all those that track broad market indexes and “smart-beta” (factor-based strategies), and classified as specialised those that invest in a specific sector or in sectors that are tied by a theme. Following is a summary of their conclusions:

Early ETFs offered broad-based portfolios at low cost. Competition for these commodity-like products has led to further fee pressure — both the iShares Core S&P US Total Market ETF (ITOT) and Vanguard’s Total Stock Market ETF (VTI) have expense ratios of 0.03 percent.

As competition became more intense, issuers started offering specialised ETFs that track niche portfolios and charge high fees — providing the opportunity to preserve higher margins.

In the market for broad-based products, ETFs hold large portfolios and compete on price by offering similar portfolios at a low cost. In the specialised segment, ETFs hold undiversified and differentiated portfolios and charge higher fees.

The median broad-based ETF held 247 stocks, while the median specialised ETF held 53 stocks.

Broad-based ETFs charged lower fees (35 basis points) than specialised ETFs (58 basis points)—supporting the conjecture that providers of specialised ETFs compete on quality by offering portfolios that are concentrated in smaller, and hence riskier, portions of the market, while charging a higher management fee for their service.

While the specialised ETFs managed only 18 percent of the assets under management, they generated about 36 percent of the industry’s fee revenues.

Specialised ETFs hold stocks whose main characteristics — high past performance, media exposure, positive skewness, and sentiment — are appealing to naive retail and sentiment-driven investors. While institutions owned about 43 percent of the market capitalisation of broad-based ETFs in their first year, they owned only about 0.4 percent of the market capitalisation of specialised ETFs.

After their launch, the specialised ETFs perform poorly as the hype around them vanishes, delivering negative risk-adjusted returns.

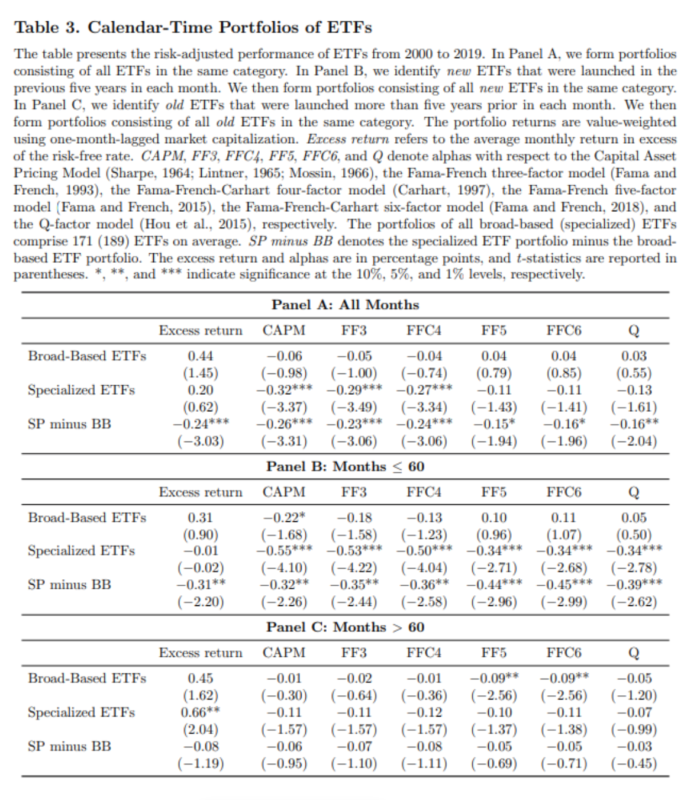

A portfolio of all specialised ETFs earned a negative risk-adjusted performance of 3.1 percent per year after fees. This underperformance was due mostly to newly launched specialised ETFs, which lost 5 percent per year in risk-adjusted terms (or relative to the market). In comparison, the risk-adjusted performance of broad-based ETFs was statistically indistinguishable from zero.

The 3.1 percent negative alphas of the specialised ETFs were about 2.5 percent greater than their expense ratios—higher fees didn’t explain most of the poor performance.

The underperformance of specialised ETFs was concentrated in the five-year period after launch. After that, their underperformance was much lower and was indistinguishable from zero.

Their findings led the authors to conclude that financial innovation in the ETF space has followed two paths: “broad-based products that cater to cost-conscious investors and expensive specialised ETFs that compete for the attention of unsophisticated investors.”

They noted: “Flows to broad-based ETFs display a significantly higher sensitivity to fees, whereas flows to specialised ETFs are unrelated to fees and respond more strongly to positive past performance.” They added: “Overall, our findings suggest that the most important financial innovation of the last three decades, originally designed to promote cost-efficiency and diversification, has also provided a platform to cater to investors’ irrational expectations.”

They noted that the stocks that the specialised ETFs owned had experienced recent price run-ups, recent media exposure (especially positive exposure), high analyst growth expectations, positive skewness (lottery-like distributions) and in general displayed traits that were previously shown to indicate overvaluation (high market-to-book and high short interest).

They added: “The investor clientele of specialised ETFs has a greater fraction of retail investors, who are typically considered less sophisticated.” They also noted that “specialised ETFs are very popular among sentiment-driven investors, i.e., those that trade through the online platform Robinhood, which has become famous in recent years for hosting investment frenzies.”

Summary

The above findings demonstrate that the ETF industry is great at capitalising on the naive retail investors for investment fads. In general, they are mainly issued in response to the demand for trendy investment themes — the fund sponsors are responding to investor sentiment, which studies such as Global, Local, and Contagious Investor Sentiment, The Short of It: Investor Sentiment and Anomalies, Investor Sentiment and the Cross-Section of Stock Returns and Investor Sentiment: Predicting the Overvalued Stock Market have found to be a negative predictor of future returns. The high fees and cash flows into these poorly performing securities is just another example of retail investors behaving badly.

Another insight provided by the authors is that sophisticated investors can detect the overvalued segments of the market by looking at the segments in which new ETFs are launched.

While broad-based and factor-based ETFs have brought the benefits of lower costs and greater tax efficiency to investors, the specialised ETFs have created negative value — except for their sponsors, of course.