The risks of highly concentrated equity portfolios

- Robin Powell

- Jul 12, 2022

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 12, 2024

By LARRY SWEDROE

While investing entails taking risks, investors need to distinguish between good risk and bad risk. Good risk is the type that you are for taking in the form of greater expected returns. For example, equities are riskier than fixed-income investments. Therefore, equities must investors for that greater risk by providing greater returns. The risk is that the expected does not occur—the higher expected returns are not guaranteed.

Bad risk is the type investors do not receive compensation for in the form of higher expected returns. Consider the case of Enron, once named by Fortuneas “America's Most Innovative Company” for six consecutive years. Its stock achieved a high of $90.75 per share in mid-2000 and then plummeted to less than $1 by the end of November 2001; it eventually declared bankruptcy. Since this type of risk can easily be diversified away, the ownership of individual stocks is one that the market compensate investors for taking. Thus, it is bad (uncompensated) risk. And because investing in individual stocks involves the taking of uncompensated risk, it is more akin to speculating than investing.

The benefits of diversification are obvious and well known. Diversification can reduce the risk of underperformance while reducing the volatility and dispersion of returns without reducing expected returns. Therefore, a diversified portfolio is considered to be both more and more prudent than a concentrated portfolio.

Despite concentrating risk in any individual company being the wrong type of risk for investors to take, many investors hold concentrated positions in single stocks — whether as the result of employee compensation or a well-rewarded stock selection. Given the benefits of diversification, why don’t investors hold highly diversified portfolios? Following is a brief list of some of the reasons:

The majority of investors have not studied financial economics, read financial economic journals or read books on modern portfolio theory. Thus, they do not have an understanding of just how risky individual stocks are and how many stocks are required to build a truly diversified portfolio. Similarly, they don’t have an understanding of the difference between compensated (good) and uncompensated (bad) risk.

Individual investors persist in their belief that they are endowed with more and better information than others, and that they can profit by picking stocks.

Investors have the false perception that by limiting the number of stocks they hold, they can manage their risks better.

Investors gain a false sense of control over the outcomes by being involved in the process. They fail to understand that it is the portfolio’s asset allocation that determines risk, not who is controlling the switch.

Investors confuse the familiar with the safe. They believe that because they are familiar with a company, it must be a safer investment than one with which they are unfamiliar. This leads them to concentrate their holdings in a few companies.

Reluctance to pay capital gains taxes.

Unfortunately, these types of mistakes can lead to tragic declines in wealth from losses in single securities. A review of the evidence will demonstrate that it’s quite common for even stocks that have outperformed for long periods to underperform, or even go under.

U.S. evidence

Hendrik Bessembinder, author of the 2018 study Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?, examined the performance of individual stocks on the NYSE, AMEX and Nasdaq exchanges over the period 1926-2015. Following is a summary of his key findings, which will likely shock most readers:

Even at the decade horizon, just 47.7 percent of stocks outperformed one-month Treasury bills, just 49.2 percent had a positive lifetime holding period return, and the median lifetime return was -3.7 percent.

Reflective of the positive skewness (lottery-like distribution) in returns, just 2.3 percent of stocks had lifetime holding period returns that exceeded the mean lifetime return.

The median time that a stock was listed on the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) database was just more than seven years.

Only 36 stocks were present in the database for the full 90 years.

A single-stock strategy underperformed the value-weighted market in 96 percent of bootstrap simulations (a test that relies on random sampling with replacement) and underperformed the equal-weighed market in 99 percent of the simulations.

The single-stock strategy outperformed the one-month Treasury bill in only 28 percent of the simulations.

Only 3.8 percent of single-stock strategies produced a holding period return greater than the value-weighted market, and only 1.2 percent beat the equal-weighted market over the full 90-year horizon.

International evidence

Jiali Fang, Ben Marshall, Nhut Nguyen and Nuttawat Visaltanachoti, authors of the study Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills in International Markets?, examined the performance of more than 70,000 stocks in 57 countries over the period 1996-2017. Their findings were similar, though even worse, than Bessembinder’s U.S. findings in that the average cross-country proportion of stocks outperforming was just 42.4 percent.

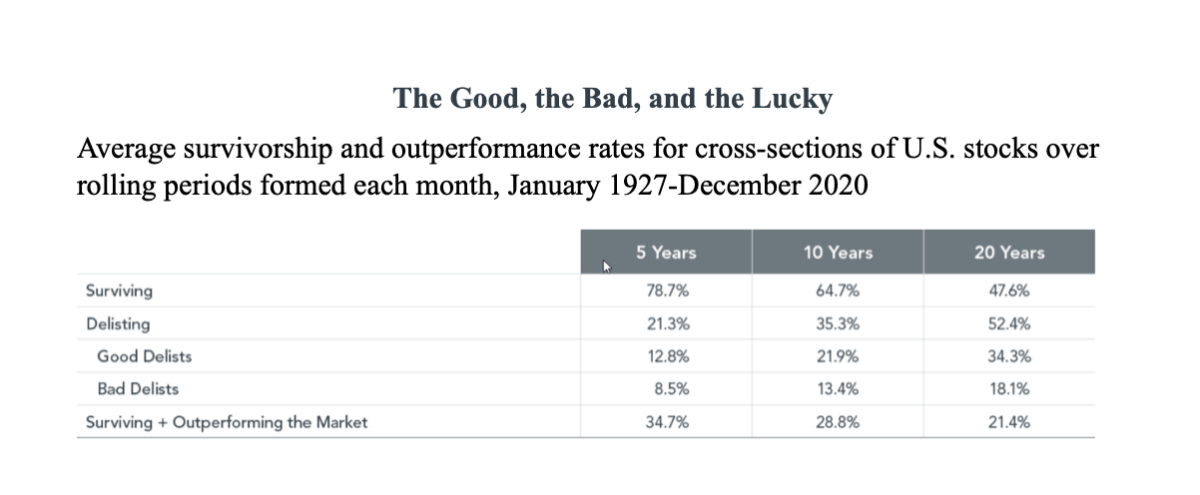

Bryan Ting and Wes Crill of the research team at Dimensional contributes our understanding of the riskiness of individual stocks with their May 2022 paper, Singled Out: Historical Performance of Individual Stocks. Among their key findings were:

Only about a fifth of stocks survive and outperform the market over 20-year periods.

Stocks delist at a high rate, even those that have been around for a long time and have outperformed the market for 20 years—the bad delist (due to deteriorating financial condition) rate is still 3.0 percent even for past outperformers.

The chance of any single stock outperforming the market in the future is not meaningfully different when conditioning on its past performance — on average, about 30 percent of the stocks that outperformed over the prior 20 years continued to survive and outperform over the following 20 years, the same 30 percent that had underperformed over the previous 20 years that went on to outperform over the following 20 years. In other words, winners have been no more likely than losers to beat the market in the future.

Investor takeaways

Most common stocks do not outperform Treasury bills over their lifetimes. The research findings highlight the high degree of positive skewness (lottery-like distributions), and the riskiness, found in individual stock returns. For example, Bessembinder noted that the 86 top-performing stocks, less than one-third of 1 percent of the total, collectively accounted for more than half the wealth creation. And the 1,000 top-performing stocks, less than 4 percent of the total, accounted for all the wealth creation. The other 96 percent of stocks just matched the return of riskless one-month Treasury bills! The implication is striking: While there has been a large equity risk premium available to investors, a large majority of stocks have negative risk premiums. This finding demonstrates just how great the uncompensated risk is that investors who buy individual stocks (or a small number of them) accept — risks that can be diversified away without reducing expected returns. Such results also help explain why active strategies, which tend to be poorly diversified, most often lead to underperformance.

The results from the studies we have examined serve to highlight the important role of portfolio diversification, which has been said to be the only free lunch in investing.

Unfortunately, most investors fail to use the full buffet available to them!

As Ting and Crill noted, the takeaway for investors is that “a well-diversified portfolio can help investors reliably capture market returns, limit individual stock risk, and improve the ability to tilt toward segments of the market with higher expected returns. Even when accounting for capital gains taxes, transitioning from a concentrated portfolio to a broadly diversified one can deliver higher growth of wealth. The long-term benefits of diversification can outweigh the short-term costs associated with liquidating outsize positions. Personalised vehicles can be used to further tailor investments, manage taxes, and suit individual considerations.”

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIV. All rights reserved. Unauthorised use and/ or duplication of this material without express and written permission is strictly prohibited.