Stories almost always trump statistics

Comments Off on Stories almost always trump statistics

By JOACHIM KLEMENT

We would like to think that investors use all the information available to them to make investment decisions. This is why the pages of the financial press are often full of statistics and data about funds, stocks or bonds. Yet, the reality is that most of the time there is a narrative driving the market or a particular stock and that narrative (or story if you like) overwhelms all statistics.

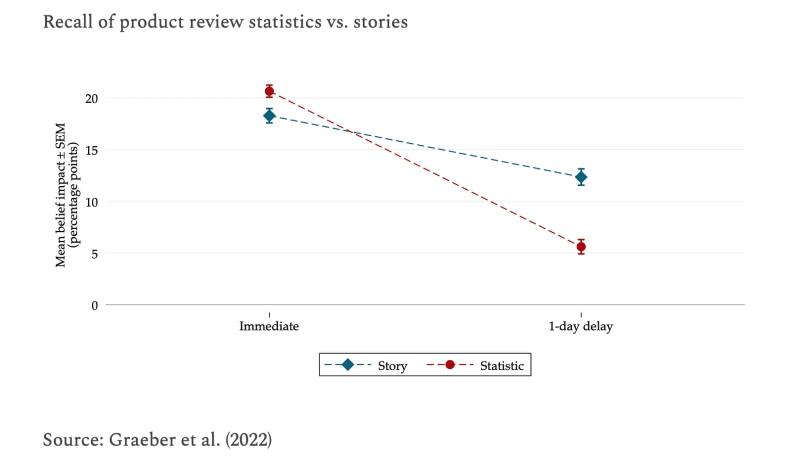

Thomas Graeber from Harvard and his colleagues used product reviews as a way to identify the influence of stories and statistics on our decisions, but I will give you an investment-related translation of the same mechanism.

Assume you are interested in buying a stock. As part of your due diligence, you look at purchases and sales of company insiders to get an idea if share prices will go up or down. After all, there is a statistically significant link between director buys and sells and the share price performance in the future.

Assume that in that company, six executives and directors bought or sold shares last month. Two of them have bought shares while four have sold shares. What do you think is the outlook for the share price?

Now assume you hear that the CEO of the company, a person who is well-known in the industry and has a high media profile thanks to his ability to make snarky, sometimes outrageous comments about the industry or his competitors decided to buy shares in his company and talked about it in an interview on investment TV. What do you think is the outlook for the share price?

You think about these two pieces of information but you decide to wait with your investment. The next day you try to remember what the outlook for the stock is. What do you think will happen?

What happens is that on the day when you are collecting the data and hearing the story, both the statistic and the story about the CEO are similarly influential on your investment decision. Both are fresh in your mind and you will be able to make decisions based on this information. But only a day later, your memory of both the statistic and the story has faded. But with the fading memory comes also a decline in influence on your investment decision. People in the lab experiments on product reviews were much more influenced by the story than the statistics in making their decision.

In our example, that might have significant consequences. The statistic shows a tendency for corporate insiders to sell their stocks and you may have decided that this is a bad time to invest in the stock. The story about the CEO, however, is a positive story that may nudge you to buy the stocks. But the CEO may not have bought stocks in the open market. Maybe the CEO was just converting stock options that vested or the CEO may buy stocks on a regular schedule. Yet, the story you remember is one of a confident CEO buying shares in his company.

And this is the problem with stories. As humans, we are naturally inclined to think in stories and we are able to remember stories much better than data. But which stories are the ones that get told? It’s the stories that are story-worthy. Stories that make you laugh or angry, i.e. stories with a lot of emotional triggers, are more likely to be told and re-told and thus have an outsized influence on investors. And these stories can for a while become the dominant story in the marketplace. Some stories last a long time before they lose their power. Just think of stories like “house prices never go down, nationwide” or “cryptocurrencies are going to replace fiat currencies”. Other stories last just a few days or weeks.

And stories are by no means always wrong. Some stories are true, some are false and some have a kernel of truth with some exaggerations sprinkled on top.

The point I am making is that as investors, we need to be aware and beware of stories. We need to be aware of them because stories can drive markets and these powerful narratives allow us to identify trends that can be exploited. But stories need to be checked with statistics in order to not fall prey to simple anecdotes that don’t tell the truth. Financial markets are full of great storytellers that can lead you astray and get you to invest your money into losing assets.

JOACHIM KLEMENT is a London-based investment strategist. This article was first published on his blog, Klement on Investing.

WHAT TO READ NEXT

If you found this article interesting, we think you’ll enjoy these too:

Two up, one down: par for the course for yearly returns

UK investors are still too heavily concentrated in UK assets

Study sheds light on cognitive dissonance in active management

INVESTING EXPLAINED — WITHOUT THE MARKETING SPIN

When it comes to investing, there is a dizzying number of complex options available.

How to Fund the Life you Want by Robin Powell and Jonathan Hollow is a new book designed to provide clear, objective guidance that cuts through the jargon, giving you control over your financial future.

The authors strip away the marketing-speak, and through simple graphs, charts and diagrams, provide investment evidence that you can use again and again. They also alert you to myths and get-rich-quick schemes everyone should avoid.

The Book is published by Bloomsbury and is primarily intended for a UK audience.

You can buy the book on Amazon, on Bookshop.org, and in all good bookshops. There are eBook and audio book versions as well.

© The Evidence-Based Investor MMXXIII