Another sign that market efficiency is increasing?

Comments Off on Another sign that market efficiency is increasing?

By JOACHIM KLEMENT

Much to the chagrin of value and contrarian investors everywhere, markets in the Western world have increasingly been dominated by momentum effect. It seems sometimes as if momentum investing is the only way to beat the market these days. One of the culprits that has often been blamed for this phenomenon is the rise of passive investing. Mindless investors buying stocks at any price just because it is part of an index eliminate the function of the market as a weighing machine of fundamentals and thus makes it less efficient.

I don’t buy into this argument at all as I have explained here. But when I read a paper from Andy Chui and his colleagues, I thought there might be another reason why momentum has become the dominating factor in stock markets.

Is it because market efficiency is increasing?

What if markets become more momentum-driven not because they are becoming less efficient but because they are becoming more so?

The research looked at momentum effects in Chinese A and B shares. The fun thing about these two markets is that the China A share market is almost exclusively accessible to Chinese investors while the China B share market is accessible to both domestic and international investors.

There are plenty of stocks that trade both on the A share and B share market, so you can investigate the price dynamics of the same stock in an environment of mostly retail investors that trade a lot on noise and aren’t that sophisticated (A shares) and in an environment of more professional and knowledgeable investors like pension funds and asset managers (B shares). But because there is no direct arbitrage opportunity between A and B shares prices on the same stock can deviate due to different balances of supply and demand.

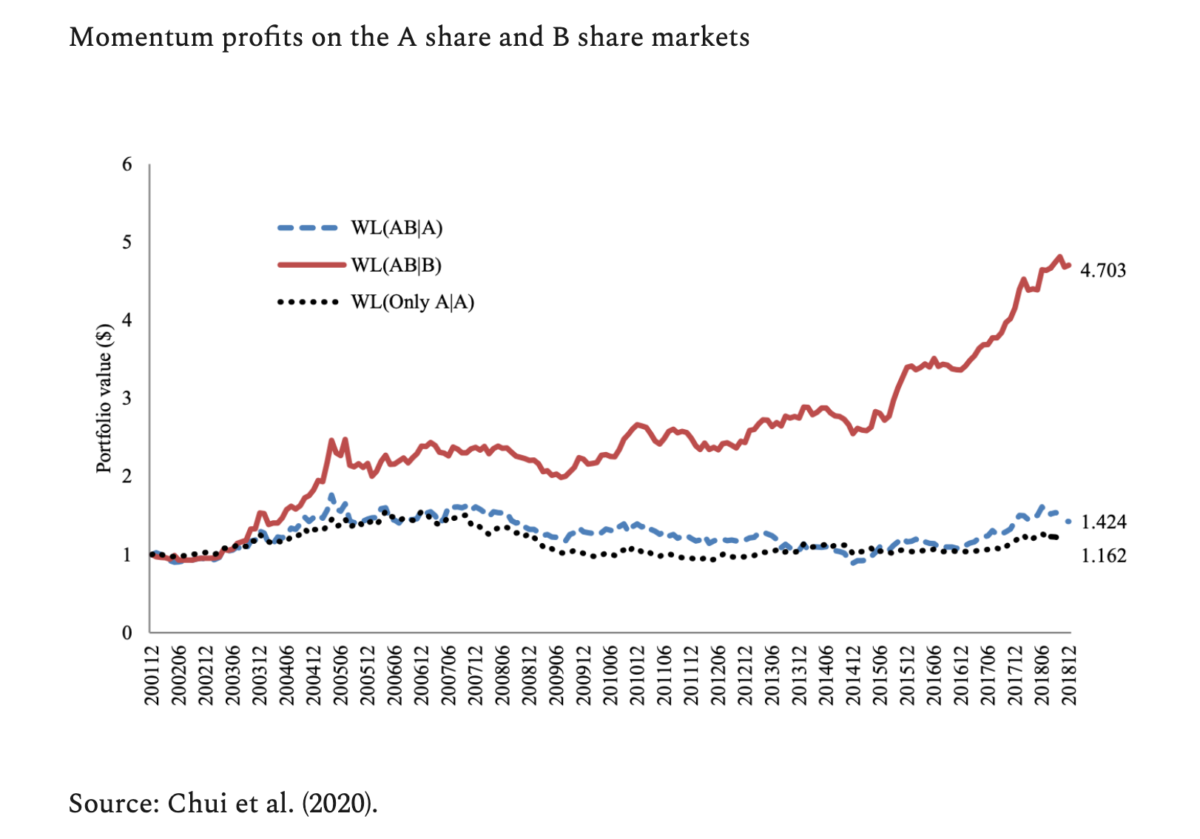

The differences are striking. The chart below shows the profits of a traditional momentum strategy Shares that trade on both the A and B share market show strong momentum effects in the B share market but not on the A share market. There simply is so much more noise trading in the A share market due to the larger number of retail investors that they destroy momentum effects. In effect, the shares that trade on both the A and B share market look very much like the shares that trade only on the A share market.

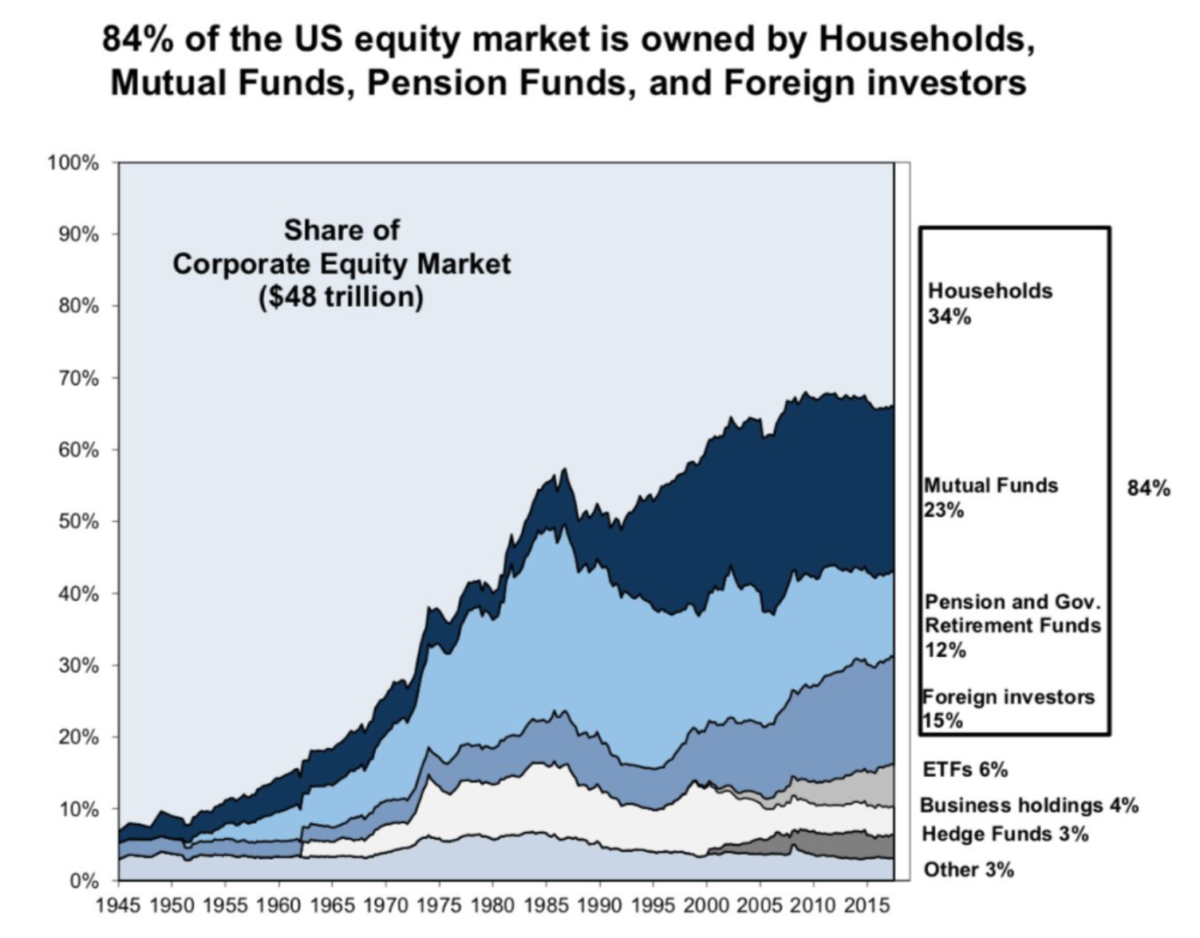

With the “professionalisation” of retail investing, more and more private investors in the West are no longer managing individual stocks themselves. Instead, they use funds and delegated mandates to have their assets professionally managed.

That means that in the West, there are fewer and fewer noise traders as well while the share of informed investors rises. And that means that a bigger share of the market is driven by professional assessments of what a stock is worth. And while professional investors constantly disagree, they are much more in agreement with each other and much less likely to stray from the herd than retail investors. And as a result, herding in the stock market increases, and momentum effects become stronger.

US stock market ownership over time (Source: Goldman Sachs)

JOACHIM KLEMENT is a London-based investment strategist. This article was first published on his blog, Klement on Investing.

Joachim is a regular contributor to TEBI. Here are some of his most recent articles:

How hard is it to find the next Amazon?

Practitioners still pay too little attention to academia

Stocks have lagged bonds since 1970. Why?

No more room at the factor zoo

Boohoo teaches ESG investors a lesson

Stop admiring your successful trades

PREVIOUSLY ON TEBI

Here are some other recent posts you may have missed:

Should investors be optimists or pessimists?

The only way to be a buy-and-hold investor

Why active will continue to underperform

Five ways to boost your financial resilience

FIND AN ADVISER

Investors are far more likely to achieve their goals if they use a financial adviser. But really good advisers with an evidence-based investment philosophy are sadly in the minority.

If you would like us to put you in touch with one in your area, just click here and send us your email address, and we’ll see if we can help.